Key points:

Formative assessment is an integral part of teaching young children.

Practice starts with the child, and grows in partnership.

Responsive pedagogy is needed to recognise what children know, understand, and can do.

Children and adults construct the curriculum together.

Observation, assessment and planning is part of professional practice.

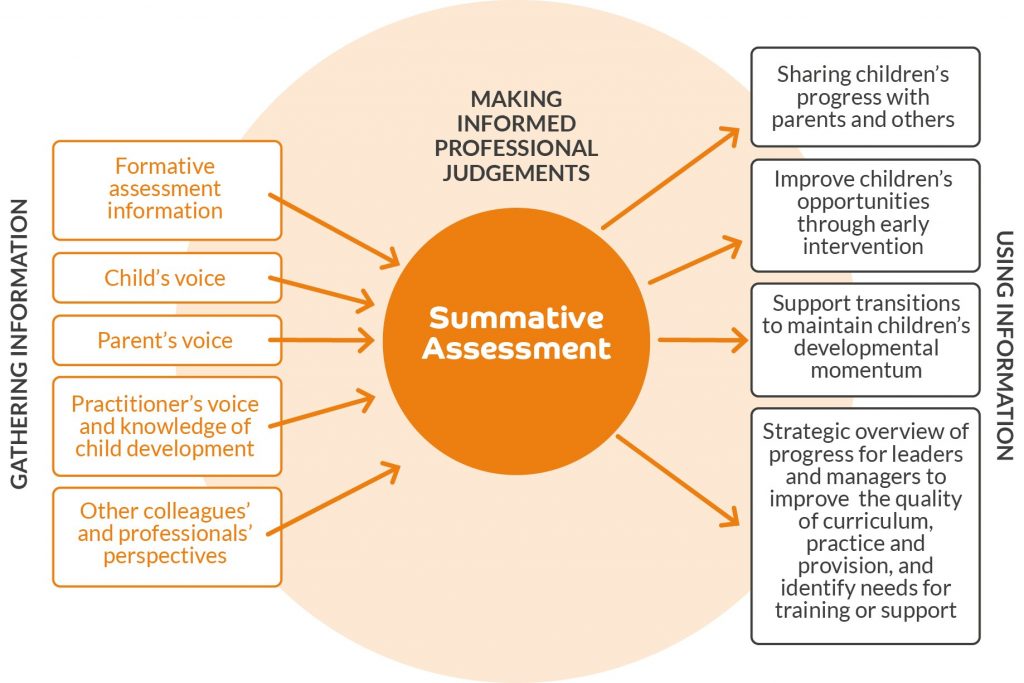

Summative assessment involves stepping back to gain an overview of children’s development and progress.

Reliable summative assessment grows out of formative assessment.

An informed professional decision is based on a holistic view of a child’s development and learning.

Summative assessment serves several purposes that can enhance development and learning opportunities for children, including by informing improvements to provision and practice in the setting.

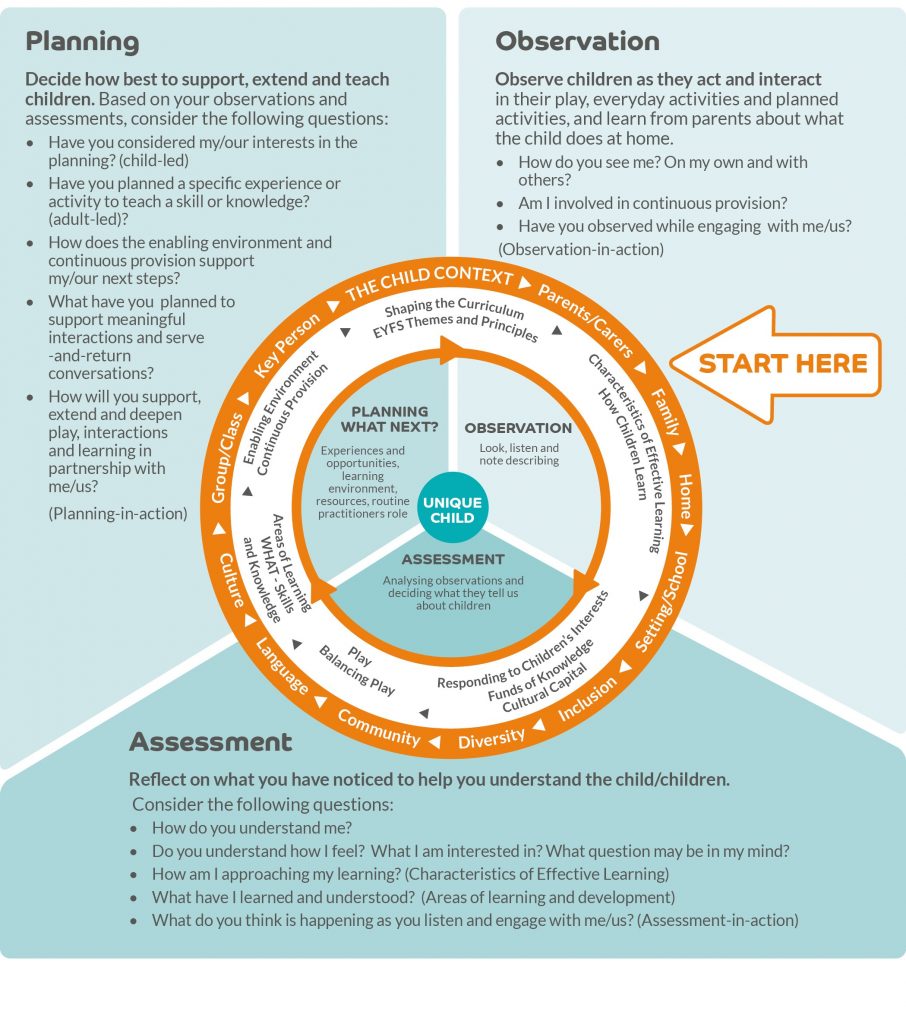

Formative assessment is an integral part of teaching young children. Children’s development and learning is best supported by starting from the child, and then matching interactions and experiences to meet the child’s needs. The observation, assessment and planning (OAP) cycle describes what is frequently called assessment for learning, or formative assessment. On-going formative assessment is at the heart of effective early years practice. It involves observation of children as a part of all activity, which is most often held in the mind of the practitioner but may sometimes be documented, using this rich information to understand how a child is developing, learning and growing, and then planning the next steps for the adults in supporting and extending the learning.

Practice starts with the child, and grows in partnership. Effective practice begins with observation, tuning into the child and then building a relationship. Professionally informed knowledge of child development then supports understanding children’s interests, development and learning, and planning for next steps. This process should involve the child, parents and carers, and other professionals.

- From the earliest age children should be involved in choices about their own learning. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Article 12 states the right of the child to express their views and have their views taken seriously.

- Parents are essential partners, sharing their views and observations about the child’s development and being involved in planning what opportunities and experiences to offer the child next.

- Working in partnership with other professionals, community and support groups connects everyone who is involved with the child and family, bringing a clearer picture of the child’s needs and rights.

Each child‘s own unique pathway of development and learning involves many elements woven together in a holistic form. Observation, assessment and planning (OAP) makes this holistic development visible, so children’s thinking and understanding can be shared with parents and carers, other professionals, and with children themselves.

Responsive pedagogy is needed to recognise what children know, understand, and can do. In a supportive and challenging enabling environment children demonstrate their learning and understanding in a wide range of contexts that have meaning to them. Responsive adults tune into their play, interactions and thinking, identifying how best to support their ideas, interests and priorities. Sensitive interactions involve listening, guiding, explaining, asking appropriate questions and helping children to reflect on their learning in a playful, co-constructive partnership. The process of OAP is central to being attuned to children and to understanding what they can do with support, as well as what they know and can do without adult direction. When children apply the skills and concepts they have mastered in a variety of different ways in their independent play and activities, their understanding is clearly embedded.

Children and adults construct the curriculum together. Keeping the OAP cycle at the heart of our practice enables practitioners to build on children’s motivations and interests to support and extend their development and learning. The curriculum is co-constructed between children, practitioners and families through this process. Children bring funds of knowledge-based interests to the setting, and they are motivated to learn through connecting new experiences to what they already know and can do. Practitioners can support these interests while also keeping in mind that they need to introduce children to new ideas and knowledge and sensitively support and guide their learning in all areas, including the Characteristics of Effective Learning.

The curriculum will include attention to the Areas of Learning and Development which summarise some of what children learn. The curriculum must, however, be more than a list of skills and knowledge to be achieved. The EYFS principle says every unique child is “constantly learning”. Children learn from all their experiences, not just those that have been planned or intended. The curriculum needs to take account of children’s learning not just in the Areas of Learning and Development, but also in how they see themselves as learners and how they are building the strong foundations for lifelong learning described in the Characteristics of Effective Learning. Howchildren learn, and how they learn about their own learning, should also be an integral part of the curriculum. Observing how children learn often helps practitioners to see what children understand.

Observation, assessment and planning is part of professional practice. Throughout the OAP cycle and summative assessment, informed decisions about the child’s development, learning and progress need to be as objective as possible, calling on the variety of information about the child to make a “best-fit” decision. The OAP cycle is a reflective and ongoing process which enables consideration of children’s development and how to support individual children through effective practice. It supports quality improvement as practitioners use their knowledge, skills and evidence gathered from OAP to reflect on the quality of education and care the children receive, and think about how to improve practice.

Summative assessment involves stepping back to gain an overview of children’s development and progress. When daily interactions involve observing, reflecting and deciding how best to support a child, practitioners hold in their mind many details of each child’s development and learning. At certain times it is important to step back, to pause and reflect, and create a summative assessment which takes a holistic overview of the child’s development, learning and progress.

Summative assessments are made to provide a summary of a child’s development and learning across all areas. There are two statutory summative assessment points in the EYFS – the 2-year-old progress check, and the EYFS Profile at the end of the EYFS. Settings may decide on further summative assessment points.

Reliable summative assessment grows out of formative assessment. Summative assessment should not be a time-consuming process. It should be a straightforward summary, pulling together insights from formative assessment and then making a professionally informed decision about the child’s development and learning. It requires a pause to think about what is known about the child, together with reviewing any notes, photographs or other records that may be held, alongside what is known from the child, parents, colleagues and other professionals. This process is an excellent opportunity for professional reflection and discussions with colleagues to moderate decisions about progress and build a stronger understanding of children’s development in all aspects of learning.

An informed professional decision is based on a holistic view of a child’s development and learning. Young children’s development does not follow a predictable step-by-step sequence, and each child will have their own unique pathway, progression and momentum. There are, however, some aspects of development which enable you to describe the child’s progress in terms of whether it is typical for their age, for example learning to talk. Practitioners need to consider overall development within these aspects and not rely on matching every element in a list of statements to judge children’s progress. It is important to take a holistic, professionally informed view to determine whether a child is roughly on track or developing more slowly or more quickly in particular areas. A holistic summary will give attention not just to areas of knowledge and skills, but also to the child’s emotional wellbeing and connections, and development of attitudes and dispositions for learning (Characteristics of Effective Learning).

Summative assessment informs improvements to provision and practice, to enhance children’s development and learning. Leaders and managers can use the information strategically to improve provision and practice. For example:

- Are some children not as far along or significantly ahead in their development and learning compared to most children? How are we further supporting these children?

- Should opportunities, resources or support within some areas of the curriculum be improved?

- Is there a professional development need for individual staff members, or the setting as a whole?

Information can be communicated clearly in a summary form to inform discussions with parents, other agencies, or professionals involved with the child and family. Transitions can be supported so that children’s journeys of development and learning continue smoothly.

Previous page: The wider context | Next page: Overview of Characteristics of Effective Learning and Areas of Learning and Development